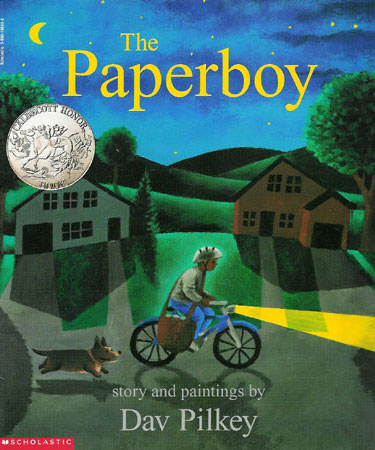

Can an illustrator write a good story? The Paperboy knows that’s the wrong question to ask. Instead, the book shows some gorgeous illustrations, while its text just fills in the details. It’s a wonderful example of two art forms combining. Dav Pilkey illustrates his interpretation of a dark neighborhood seen by a newsboy – while Dav Pilkey the author contributes a story which weaves it all together

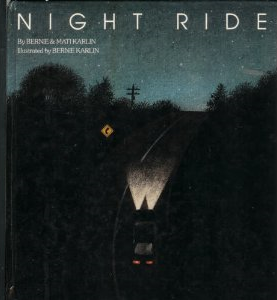

But it’s the illustrations that are really the star of this book. The title page shows a grey truck leaving the printing building on a dark night. There’s a beautiful two-page drawing of the empty field that truck will pass. Shades of green suggest gentle moonlight, and so do the softened edges on the houses. The sky has turned dark blue, but on the next two pages it’s becoming purple. And the truck parks by some rows of colorful houses which represent the sleeping city.

The paperboy sleeps with his dog – which gives the story a crucial warmth. The boy doesn’t want to get up, but the next page shows his room filled with his lamp’s yellow light. The sleepy boy shuffles alone past the rooms where his family is still sleeping. But at least his pet keeps him company, and the boy and his dog head to the kitchen “where they eat from their bowls.” There’s even a whole page about the dog view of the paper route. (“He knows which trees are for sniffing,” and “which birdbaths are for drinking,” and of course…which squirrels to chase!)

I think it’s a good story, because it captures the best lessons of the paperboy life: that even a child can shoulder a responsibility, and play a role in the neighborhood’s life. The boy puts rubber bands around the papers. And though it’s difficult to ride his bike, he manages. But there’s also a quiet celebration of the joys of being alone. Sometimes the paperboy thinks about big things, and sometimes he thinks about little things. And sometimes, “he is thinking about nothing at all.”

“All the world is asleep except for the paperboy and his dog. And this is the time when they are the happiest.” It’s the same lonely message that Robert Frost shares in his darkest poems. Unfortunately, “little by little, the world around them wakes up.” The sky turns a brilliant orange, and back home, he hears the sounds of his family waking up. But he crawls into his bed, and now carries the pride deep inside of him. He dreams that he’s flying back into the nighttime sky.

And his dog flies with him too.