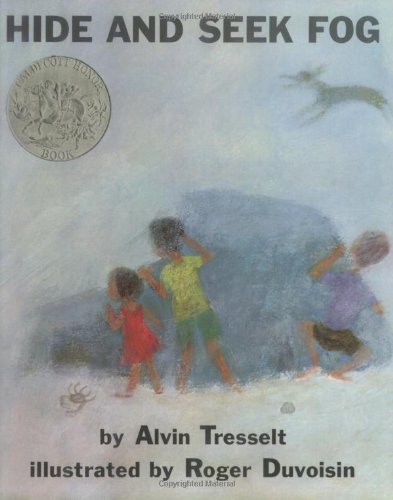

Alvin Tresselt wrote beautifully about natural subjects – like snow and heat – and the way they influence the world around them. (“A Gift of the Tree” described the entire life cycle of a dying oak tree, and the way it nourishes the ground around it.) “White Snow, Bright Snow” won a Caldecott Medal for its illustrations in 1948. Sixteen years later, Tresselt tried a similar formula. But this time, his book was about fog.

“The lobsterman first saw the fog as it rolled in from the sea,” the book opens “He watched it turn off the sun-sparkle and the waves, and he saw the water turn gray.” Tresselt writes poetically about the gradually creeping cloud, describing how it turned the water gray and made the boats bob like corks. But he also writes about the people it affects, and the book lists out every reaction.

“The dampness touched the crisp white sails of the racing sailboats, and suddenly the wind left them in the middle of the race.” Seagulls, too, respond to the fog, return to nests on the craggy rocks. Vanishing into a fog bank, even the sun becomes “a pale daytime moon.” And families on the beach hurry to gather up their picnic baskets.

The illustrations are beautiful, with a bright gray that makes everything seem soft and abstract. It’s the same illustrator Tresselt used 16 years earlier on “White Snow, Bright Snow,” and those illustrations won a Caldecott medal. Roger Duvoisin uses an entirely different style for this book, and most scenes are shown through a gentle blanket of fog. But in other drawings, the colors of the city are visible, like when the lobsterman hurries his catch off the fishing wharf. And there’s a cheerful red floor when the children make scrapbooks by a warm driftwood fire.

The lobsterman hears “the mournful lost voices of the foghorns,” but he’s stuck at shore working on his lobster traps. The fathers complain that their vacations will be spent in a foggy cloud. On the streets, people with bundles accidentally bump into each other. And the children play hide-and-seek among the foggy rocks.

It’s surprising how this simple story can become so intriguing. It’s the worst fog in 20 years, and it lasts three days. But then there’s a sudden warmth in the fog, and the sun finally pierces the veil. The water sparkles again, and the islands in the bay are lit by gold. Then everything returns to normal – the lobsterman fishes, and the children play on the beach.