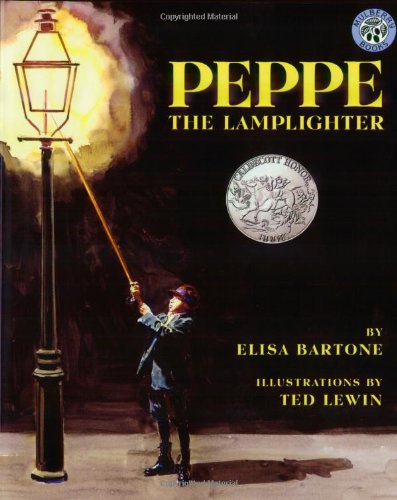

It’s loosely based on a story about the author’s Italian grandfather. (Elisa Bartone’s grandfather immigrated to the United States from a town near Naples, according to the book’s jacket.) She dedicates Peppe the Lamplighter to the memory of her grandparents and her father. And illustrator Ted Lewin just dedicates it “to the American Dream.”

It’s a sad story about Peppe, who lives in a tenement. His mother is dead and his father is sick, and “he had to work to help support his sisters: Giulia, Adelina, Nicolina, Angelina, Assunta, Mariuccia, Filomena, and Albina.” The last sister still lives in Naples with her uncle, a priest who runs the orphanage. Peppe visits the shops in Little Italy, hoping to find a job.

Illustrator Ted Lewin “has loved Little Italy since he first moved to New York,” according to the book’s jacket, and he draws beautiful pictures of the people in Peppe’s neighborhood. There’s a white-haired butcher (with a bristly moustache and a top hat), and “Fat Mary” who makes the cigars. A bar full of businessmen even watch as Peppe asks Don Salvatore, the bartender, for a job washing glasses. And word finally spreads to Domenico, the skinny lamplighter, who says he’s “going back to Italy to get my wife.”

Lewin’s illustrations bring the story to life, including touching pictures of the boy’s family waiting for him at home. But Bartone’s text gives each character a real personality. “Did I come to America for my son to light the streetlamps?” the proud father rails. And after he slams the door behind him, all the sisters contribute different words of support. “It’s a GOOD job, Peppe,” says his sister Assunta.

Peppe walks down the street at twilight, and opens the glass of each streetlamp to light it, and the description makes it seem exhilarating. Bartone describes it as a “joyful” feeling, and the boy imagined each small flame to represent promise for the future. “It was almost like lighting candles in the church for special favors from the saints,” Bartone writes, and the boy makes wishes for each of his sisters.

“This one for Giulia, may she have the chance to marry well… This for my mother, may she look on us with pleasure…”

The angry father heckles him from the window, while even Fat Mary tries to coax him to smile. But one night Peppe doesn’t go to work – and his little sister gets lost in the dark. The father agonizes over his missing bambina, and finally has a change of heart. “‘The streets are dark, Peppe… Tonight the job of lamplighter is an important job. Please, Peppe, light the lamps.

“You will make me proud.”