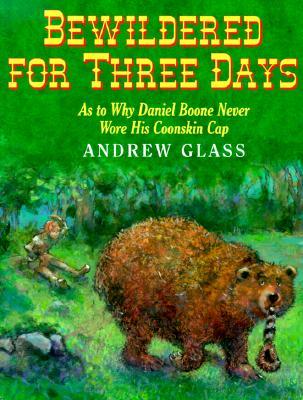

What do Buffalo Bill, Kit Carson, and Johnny Appleseed have in common? They’ve all appeared in children’s books by Andrew Glass. But in 2000, Glass turned his attention to Daniel Boone, the famous Kentucky frontiersman. Glass starts with a true piece of history – that Daniel Boone never actually wore a coonskin cap – then invents a tall tale that explains why!

Writing about Indians is a delicate subject, but Glass finds a way to have it both ways. A young Daniel Boone farms a “hardscrabble” field with his brothers, they’re suddenly surprised by a tribe of Cherokees. Glass writes their “warriors burst through the trees, shrieking and waving hatchets.” But it turns out they’re friendly Indians, who have come to protect them from a more hostile tribe. “It was only a terrifying misunderstanding,” explains Daniel Boone’s mother.

Glass’s illustrations are almost impressionistic, with bright colors, almost like an American Gauguin. It seems oddly appropriate for a story set in the mid-1700s. Glass mixes some real history into his tale, and soon the Indian’s son is telling Daniel Boon about a fertile farming land that waits beyond the dark mountains. And Glass drew a funny illustration of Boone waking in the woods, only to discover a hairy bear standing over him.

It’s difficult to be both the illustrator and the author, and Glass sometimes offers too many details. He devotes a whole page to Boone’s thought process, explaining why he decided to chase the bear who had stolen his coonskin cap. But Glass seems determined to present a sympathetic explanation for the Indians’ hostility. (“The Delaware [Indians] live in the forest and love the savage wilderness as their mother. When we ask them to honor our fences, it is an unreasonable thing we ask.”)

There’s some exciting scenes, like when young Daniel Boone jumps off a 60-foot cliff to escape an attacking tribe of Indians. (The Indians gawk as Boone lands in a tall tree, while the text explains the rest of Boone’s escape.) Boone ends up hiding in a hollow log – all night – while the tribe of braves camps for the night, never realizing how close he is. Boone intrudes on a family of raccoons, and to thank them for his hide-out, he promises, “sure and solemn: I will never again wear any of your kin on my head.”

In an author’s note at the end of the book, Andrew Glass admits that Boone probably just preferred wearing a wide-brimmed hat. But he thought a promise to raccoons would be more dramatic!