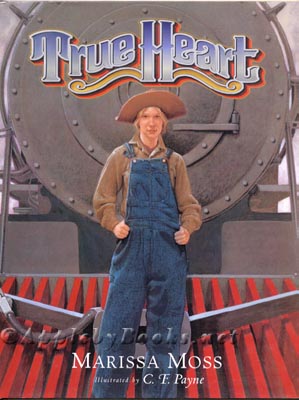

“It makes me grin, because my wish came true.” There’s real history in True Heart, a children’s book which was inspired when Marissa Moss visited the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento. A frontier engineer remembers back to 1893, when they were a teenager who could only dream about driving the railroad. There’s a real love of trains in this book – but also a good story about following your heart.

The first page shows an old-fashioned lamp by a black-and-white photo from the past. The engineer describes it as their favorite photograph, because he reminds him of his youthful dreams. “It’s good to remember wanting something so much you can’t think of anything else,” Moss writes. Their parents had died, and they’d gone to work for the Union Pacific at age 16.

The book offers the engineer’s story while sprinkling in bits of American history. (“When my parents came out to Cheyenne from Minnesota, there wasn’t any way to cross this country except by wagon…”) And Moss obviously remembers details about the Sacramento railroad museum. She captures some of its magic, writing that the locomotives are “gussied up with curtains and lace,” and the engineer loves to hear “their clatter and roar.”

The young narrator befriends an engineer, who answers questions and even let’s them back up the train. But it wasn’t until I read the book’s last page that I realized the aspiring engineer was a female. Her friends teasingly call her “Engineer Bee,” but her big moment comes soon. The girl volunteers to drive the train after robbers wound the regular engineer. The station manager won’t let her, but an important banker intervenes. The next page shows the girl in the engine’s cab, as the manager calls out “You’re an engineer today.”

I think Moss does a good job of combining her story with all the details of railroad life. Bee loves the sound of the whistle, “Like the wind blowing down your back.” On her big day, the people on the platform get smaller and smaller as the train “stuttered” out of the station, making sounds like “tickety-tack, tickety-tack” and “chuff-chuffing.” The prairie grass “ripples” by the train, and it passes herds of buffalo “like black patches on a yellow quilt.”

“It was just like I always dreamed it would be.”

Illustrator C.F. Payne created five stamps for the U.S. Postal Service, and is a famous illustrator (according to his Wikipedia page). I like how he put the book’s title in an old fashioned font, with fancy seraphs and a decorative curlicues. There’s a great title-page drawing showing the train’s twin rails stretching off towards green Sacramento mountains. And he draws Bee as so much of a tomboy, that her story could belong to either gender.

Moss reveals that she’d seen a photograph of female railroad workers at the museum, and some historical research revealed that women really had worked as engineers. But both boys and girls should enjoy this story, and be inspired by the fulfillment of one teenager’s dream.