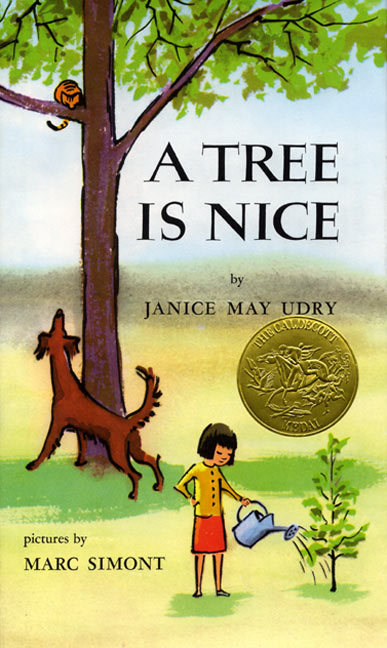

It won the Caldecott Medal in 1956 – but the pictures are timeless. Marc Simont illustrated two of James Thurber’s books, according to the book’s jacket, and had also written and illustrated several books of his own. For A Tree is Nice, he teamed up with Janice May Udry, who grew up in “a city famous for its elm trees.” After leaving Jacksonville, Illinois, she’d moved to the south, where she searched for a beautiful tree that could grow quickly – and for Simont’s next project, she wrote about trees.

“Trees are very nice,” the book begins. “They fill up the sky.” But it’s not a story as much as an open-ended meditation. Simont draws a boy fishing in a stream, as Udry writes that trees are found by rivers, and also on hills. “Trees make the woods,” she writes simply, and feels compelled add a personal response. “They make everything beautiful.”

There’s a sketch of a child in the crook of a tree’s branch, and a title page illustration that looks like a cartoon. Throughout the book, Simont switches between color and black-and-white white illustrations, which makes each drawing a little more surprising. There’s a horse in the shadow of a tree, with the white page representing a bright field. And the next page shows brilliant autumn colors, with reds and yellows in the leaves of the trees.

Udry lists out the things you can do with a tree. You can play in a pile of leaves, or rake them into a bonfire. You can climb it, or pretend it’s a ship, and if it’s an apple tree, pick it’s fruit! “Cats get away from dogs by going up the tree,” Udry adds “Birds build nests in trees and live there.” They’re all facts that we’ve heard before, but it’s strangely ompelling to see them collected together.

“Sticks come off the trees too. We draw in the sand with the sticks.” The book has a simplicity that’s almost zen-like, as Udry simply continues listing out the uses for a tree. “A tree is nice to hang a swing in… It is a good place to lean your hoe while you rest.” It’s a fond book, and enthusiastic – and Udry resists the pressure to dream up a story. It takes a certain amount of integrity to simply share all the details, and let the trees speak for themselves.

There’s three pages about shade – with trees sheltering cows, houses, and even people on a picnic. “The tree holds of the wind and keeps the wind from blowing the roof off the house…” But the secret agenda of the book lies in its final pages, saying that a tree is nice…to plant.

Udry ultimately says that planting a tree makes other people want to plant one themselves.