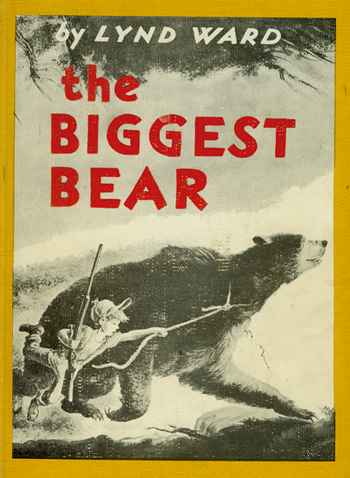

He illustrated 200 children’s books, and was the illustrator for “Johnny Tremain.” The book’s jacket even describes him as “one of America’s greatest artists.” But in 1952, Lynd Ward started his greatest project. He both wrote and illustrated the story of “The Biggest Bear” – and it won him the Caldecott Medal.

“Johnny Orchard lived on the farm farthest up the valley,” Ward writes, “and closest to the woods.” He draws the boy’s smiling face, and then an illustration of his grandfather’s farm. But the third drawing shows the source of the boy’s humiliation: all the other farmer display a bear skin nailed to the side of their barns. In fact, Mr. Pennell had impressed the boy by shooting three bears once when they’d passed by his field.

If this book is problematic today, it’s only because it shows drawings of the hunters pointing their guns. But Johnny’s grandfather seems less militant, and tells the story of encountering a bear – and then running. “Better a bear in the orchard than an Orchard in the bear,” he jokes. However, Johnny finds this humiliating, and vows he’ll shoot a bear himself if he ever comes across one.

Ward obviously liked the idea of drawing the small boy in the wild woods. But he’s also dreamed up a clever surprise for his story when the boy ventures in with his gun. Johnny discovers a tiny bear cub instead, and gives it a piece of maple sugar. He cradles the bear in his arms, and takes it back to his family. And soon they’re feeding the bear cub on the milk from their cows.

The calves look on angrily, since that milk was meant for them. And the cub also likes the corn mash that was “meant for the chickens.” Each sentence gets a wonderful illustration, as Ward lets the story unfold. The cub “liked the apples in the orchard,” he writes – then shows the upside-down bear climbing a branch for the fruit!

The cub likes pancakes on Sundays, and Johnny’s maple sugar. And “Johnny’s mother got pretty upset when he started looking for things on the kitchen shelves.” One night the bear camps in a neighboring farmer’s corn field. And Mr. Pennell’s smokehouse was soon plundered for its hanging hams. Picture after picture details the havoc that was wreaked by the visiting bear.

He guzzles syrup in a shed, and even the sap tapped from the maple trees. “He was a trial and a tribulation to the whole valley,” the neighbors explain to Johnny’s father. They lead the bear back into the woods – but the bear simply returns to the farm. Ultimately Johnny decides that he has to shoot the bear after all…even though now he doesn’t want to. But fortunately, the book finds a happy ending instead, and the bear is taken off to the zoo.

And whenever Johnny goes to visit him, he always brings maple sugar.