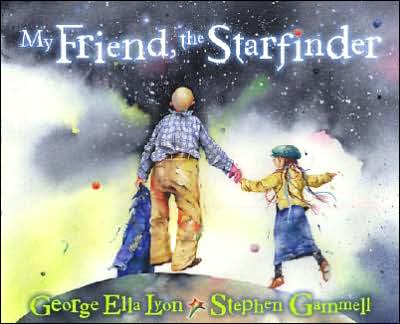

George Ella Lyon is one of my favorite writers, but there’s some surprising illustrations in “My Friend, the Starfinder.” Stephen Gammell contributes amazing watercolors showing the wonders of the night sky, adding a glorious background for even the simplest sentences. It’s a fascinating combination of two artists – a writer and illustrator – and there’s an exciting interplay between the two as the story moves along.

Lyon describes an old man in a ragged suit – but the illustrator fills his jacket with wild colors. The colors almost steal the show, as the side of his house is filled with greens, pinks, and purple. “He wore old soft clothes and sat in and old chair on an old green porch and told stories,” Lyon tells us. On the next page, a meteor shines through a green universe… But then the watercolors switch to rich grays and whites when the old man begins telling his story to a little girl.

Even with blacks and grays, he somehow creates a magnificent sky filled with planets and stars, its dark clouds swallowing trees on a hill. The shades create levels and depth behind twinkling stars, even on the title page where the author and illustrate dedicate the book to their loved ones. I’ve never seen black and white watercolors before, but they’re surprisingly effective. The illustrations show the old man’s memory of following a star across a field when he was a young boy.

When Lyon writes that the boy kept walking, Gammell draws a breath-taking cumulus cloud, stretching across the sky with black edges in a bright white sky, dwarfing the tiny fence in the field below. When the boy reaches the top of an inky hill, there’s a splotch of yellow and spectacular stars in the sky. Lyon writes simply that the boy “picked the star up,” and Gammell imagines a big star-shaped rock, its grays flecked with gold and turquoise. And when he hands the star to the little girl, the two friends are filled with colors, and a ray of sunshine peeps through the gray clouds.

In another story, the old man’s hand turns purple – and Gammell draws mysterious tangles of branches and tree trunks. I like Ella’s simple words – she describes one color as simply “orangey orange as fire” – and it turns out the man had wandered to the end of the rainbow, discovering “cool warm striped air.” But the illustrations give the story a vast perspective – showing the mountains in the valley as a pastiche of colors with white wisps and a yellow streak of sun.

And Lyon writes that she could feel all the colors.